Peter Daly - Moved by the spirit

"I remember playing at Fred's Cafe once on the piano. The piano started rocking and I looked down and I had blood coming out from under all my fingernails so obviously I was playing pretty hard. And then all of a sudden the piano collapsed and fell on its back. It was amazing it didn't actually crash through the bloody floor. I must've been so amped up that I just picked the piano up, stood it up again and kept playing. I've never been able to lift a piano since." - Peter Daly

Viola player Peter Daly has been one of the most consistent improvisers in Wellington since the late 1970s. Charting his own course through the wild waters of improvisation, drawing on his background in classical and folk music, Peter maintains meticulous and subtle control over the viola. But when he's playing he is open to being moved by the spirit of music. Not only has he pushed over pianos, one time he was in the middle of performing Bach and found himself jumping up and down on top of his violin. I caught up with Peter in his flat which hovers over the southern suburb of Strathmore.

Why did you jump on top of your violin?

Probably over-rehearsal followed by stimulants, and instant disappointment at my performance, sort of a toxic combination. I jumped on a few instruments. That was the whole era where people were admired for killing themselves and jumping on their instruments and all the rest of it. Some sort of mythology which is all rubbish. But the level of frustration was extreme, to do with my relationship with classical music. I would play solo a lot, and for some strange reason I had this idea ingrained in me about being a solo channel for the divine to come through. I became obsessed by Bach's solo music and anything 'unaccompanied'. I use that word 'unaccompanied' in inverted commas because it's not really unaccompanied. Even if it is only a solo line it'll have all the implications of the harmony to be filled in by the listener. Solo melody can move you in a way that an accompanied one cannot. This is why in many respects orchestral music deprives the listener of any innate response because it's all spelt out for them. But I always had a feeling that it is possible to achieve some spiritual state in which you are channeling creative energy. That came from a very religious background. I also did quite a lot of experimenting with Eastern thought, and I believed it was possible to be a channel for the spirit to speak through music.

How do you tend to approach the start of a performance?

Rather like jumping off a diving board. I have been known to wait for something to happen and then respond, but I've come to prefer the diving board approach. Not necessarily the high board, but with a reasonable amount of just jumping into it. I play with one person regularly where we've been jumping in together. That's quite interesting because, by starting together, immediately, the result depends entirely on the random permutation that emerges at the beginning. It's like throwing coins in a way, you just jump into it, and from there on you can build. I quite like things that start and finish. One of the difficulties with improvised, free music, it can sometimes take ages to get going and ages to stop, and somewhere in the middle it's really good. But sometimes there's a meandering sense of lack of momentum or lack of presence. That's something I've tried to avoid. I prefer the diving board thing, just jump into it.

You've got this tension immediately between what you're doing and what someone else is doing and how that resolves, or doesn't.

And the atmosphere, the audience present, and the vibe in the place is something that you're immediately picking up on. I really do believe that audiences create a lot of free improvisations, they're an active force. So there's very good sense not to have any package in mind before you start, because then you can actually pick up on all the subliminals of the atmosphere. It's hard to quantify, it's just there, but it does definitely affect what you do. I often feel improvisers ignore and internalise what they're doing, and even ignore the people they're playing with, which is one approach but not necessarily my favourite. It's quite difficult to perform an improvisation in the sense that you're not reading a story that you're going to apply various expressions to to make a point, so you don't have a dramatic reality. But at the same time I have found it's still good for me` to be able to get a sense of whether the audience is engaged and if they're not I'll probably do something extreme, something to wake them up, something confronting. You get some audiences and they're sitting back, end of the working day, not active listening. I think audiences now have often listened to so much music in the background they have the tendency to be quite passive in their reaction to how they listen to music, they're just there and you happen to be there as well. Sometimes people need a wake up call to bring them into the moment.

When you're in the midst of performance, how aware are you of where you've been or where you're heading and trying to shape that narrative?

Not particularly aware at all of where I've been, and not particularly aware of where I'm going either, but I'll have a sense of balance about ideas that have gone on too long and need contrast. I have a sense of texture, from playing classical music for so many years a sense of form, balance. There's certain textures, they're nice for a while but like everything, at a point it becomes neutralised by going on too long. So contrast of texture, contrast of rhythmic variety, contrast of harmonic texture or density of harmonic texture, and then the wilful interruption of ideas, creating tension between polar opposites, that's very important as well. I try not to get too lulled into the journey. At times it's necessary to shift lanes suddenly, otherwise it just becomes an internal reverie, which is not what I'm trying to do.

Does your approach change from when there's no audience, and then playing in a concert situation?

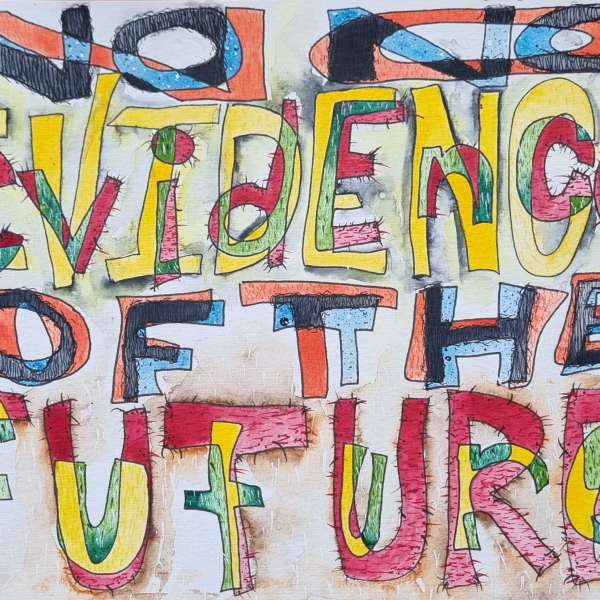

Yes I think it does, it changes a lot. I think the little bit of adrenalin is a great thing. Obviously I've had problems with it overpowering me at times. But there's a certain nowness about a performance. I've never been able to simulate it in a private situation. That's the whole audience feedback loop. It's one of the reasons I like live performance particularly. Often I've noticed playing with people how, even if they're playing live, if it's being recorded they play differently. I think there is a subtle energy, perhaps a lack of intensity because of the existence of a future recording. Even a lack of boldness. They have another monitor, some futuristic concept of how this is going to look later which is I think very uncreative and one of the dangers of recording yourself too much. Live performance for me is a celebration of the present moment and music by its nature to me is an ephemeral, intangible, unholdable entity. Although we've managed to capture it with our machines, I still feel that we've only got a reproduction and so that from a purists' point of view I can imagine a world where I never recorded ever. I remember being interviewed once and I said this ludicrous thing, I said I'd rather play for one person live than for thousands of people on recording.

Although doing it as something to aid your practice and recording a concert are two quite different situations. And that idea of when you're performing, doing it in the moment for the people there as opposed to some future audience that might be listening to it.

Everybody has their bag of tricks and it's one of the problems with improvising, you have these little ways of impressing yourself or others. They sound great but unfortunately they are a bag of tricks a lot of the time and it's very difficult not to use them when you're trying to impress people. And impressing people is one of the things that one should not attempt to do when performing. Maybe I'm being too unrealistically egoless about it but I still feel there's a much higher form of creative energy than an ego driven one. The ego is obviously a good tool, and I'm not saying that I'm trying to achieve some egoless state. I have noticed and kick myself for using my bag of tricks. Most jazz players and improvisers have it, and they know about it, but a lot of them won't admit it. And in a way it's useful, it's a tool. But if it's just applied as an easy remedy for a lack of inspiration or to suddenly remind people that your technique's really amazing, that's pretty transparent. Another aspect that I have difficulty with myself is seeing the lighter side of improvised music. It's something that I'm still attempting to come to terms with because I don't think that music should necessarily be Serious with a capital S all the time. It's lovely to hear people being playful. We say we play music, we don't work music. But a lot of the time people don't really play it, they just work it.

Peter Daly is a viola player who has been active in free improvisation for more than four decades. He is a versatile musician who collaborates with many performers including recording with Phoenix Foundation and Orchestra of Spheres and regularly plays with Simon O’Rorke, Bernard Wells and others.