Dumb enough to actually try it

Learning From the Punk Movement

More than four decades after its inception, the punk movement has demonstrated a staying power that would have astonished early observers who presumed it to be an ephemeral phenomenon.

Punk culture clearly fulfils creative and social needs in participants. However, it has also developed an economic structure and organising methodology. This not only sustains it, but has given many people skills which have proved effective well beyond the punk movement

Punk Culture and Origins

Garage rock bands playing music in the punk style and sometimes displaying some punk attitudes and values have emerged sporadically since the invention of rock. However, the development of punk as a movement didn’t begin until the late 1970s, triggered by events in the Middle East.

After the failure of Arab forces in the 1973 Yom Kippur war against Israel, Arab countries orchestrated an oil embargo targeting Israel’s Western allies. The ’oil shock’ significantly disrupted the economy of Western countries throughout the mid and late 1970s, shattering the already creaky post-World War II social contract which had provided a tolerable, though hardly luxurious, standard of living for Western working classes (a second oil shock followed the 1979 Iranian revolution, sending oil prices to a new high and further exacerbating the economic crisis in the rich world).

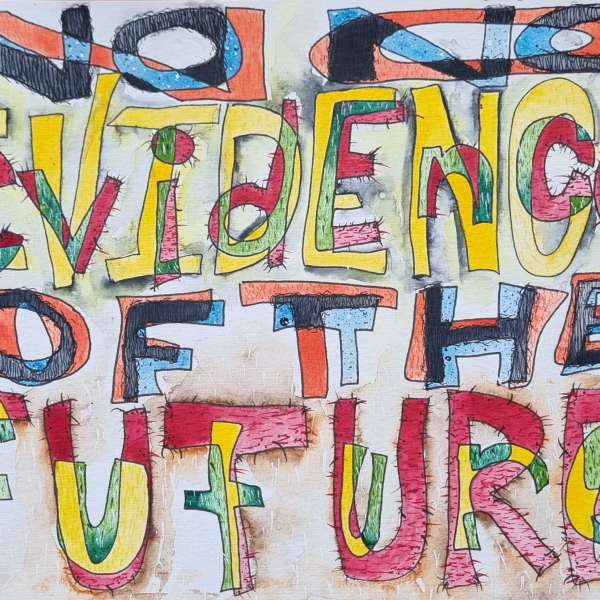

Populist right-wing governments became the norm, unemployment skyrocketed and the optimism of the 1950s and 60s vanished, replaced by a pessimism about the future and a realisation that the promised rewards of participation in the capitalist system would not eventuate. All that was on offer was a dead end job or life on the dole, and everywhere crippling boredom. The threat of nuclear war, and growing awareness of environmental degradation added to this feeling of hopelessness. These factors created the economic and cultural conditions that made the punk counter-culture attractive to a critical mass of people, enabling it to form a movement, and to establish itself with a degree of permanence.

Punk got on with the job, leaving others to theorise about it. A Marxist writer, addressing the rise of punk in 1980 in the US zine Theoretical Review, put it this way: “Recognising the potential for utilising existing cultural elements to the advantage of the working classes in the day to day class struggle within ideology is the first step toward building the hegemony of the working class in the struggle for socialism.” Nobody knows what that means, and nobody gives a fuck.

Of course, punk was not autochthonic. Punk was influenced by other musical styles such as rockabilly and reggae. It embraced particular, increasingly available technologies, such as the photocopier and cassette tape. Politically, it was influenced by socialist and anarchist thought, and especially by Situationism, a European post-Marxist current which emphasised the deficient psychological, rather than material, conditions the working class lived under. Punk’s objection to consumerism was based on society’s successful production of tedium rather than its failure to produce goods.

Punk’s politics were in part accidental, though perhaps inevitable. When John Lydon (AKA Johnny Rotten) of the Sex Pistols sang the punk anthem Anarchy in the UK on television for the first time, the show’s host Tony Wilson appeared more politically learned than the band, quipping “Bakunin would have loved it!” after the performance (a reference to 19th Century Russian anarchist activist Mikhail Bakunin which appeared to go over the band’s heads). Lydon later denied ever being an anarchist, saying the use of the word ‘anarchy’ was “just a novelty for a song”. Silly old bugger he turned out to be. Others took the politics seriously though, and ran with it.

The Punk Economy

Punk is characterised by a DIY ethic, an emphasis on participation, setting a deliberately low bar of technical standards, and a radical politics based on personal experiences rather than political theory.

Punk provides an accepting social space for many who feel themselves outsiders. The chronically shy, odd, and slightly screwed up often find themselves accepted in punk spaces. Contrary to media myths which frequently misunderstand the occasional (mostly theatrical) aggression of punk dress and behaviour, punks tend to be friendly towards anyone who isn’t overtly culturally mainstream or a complete fuckwit. Entry is easy – there is much less cultural gate-keeping than in most movements or institutions, and humour plays a significant role – not surprisingly given the movement was formed while Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were running the world and a dark sense of humour was the only way to stay sane.

It should be noted that punk frequently failed to create the inclusive movement it idealised. Some punk scenes continued to marginalise women and people of cultural, ethnic and gender minorities. Often punk did pretty well at offering an inclusive social space, but in some places and times it was a bit of a white boys’ club failing to fully challenge the establishment values it supposedly condemned.

Punk has clearly had a significant impact on art, fashion, design and music. What is less recognised is its impact as a training ground for facilitators and managers.

Opportunity

Long-term punk organiser Ross Gardiner points to the expectation of high levels of participation in the punk scene: “More than most other music-based scenes, punk is created by the fans becoming the scene themselves – actively creating what they want rather than being mere spectators. While the scene has never been huge, the proportion of bands compared to the fan-base is really high.”

Punk scenes typically have a considerable cultural output beyond just forming bands and organising gigs. Other work includes publishing ‘zines and posters, modifying clothing and textiles, screen printing and assorted other craft activities. The rarity of money and material goods means they are used as efficiently as possible.

”For myself, it's given me the opportunity to do a whole lot of stuff that I wouldn't have been able to do otherwise.” says Gardiner. “I've been in bands, put on gigs, festivals and tours for overseas bands, helped publish and distribute zines and recorded music, screen-printed t-shirts and patches, and helped with radio shows. Of course how much you learn depends on how much effort you put in, but if you don't have that opportunity to do things in the first place then you wouldn't even get started.

“A lot of what I learned at school seemed a bit abstract, and I couldn't see a way of using it in real life. And while organising punk events started off purely as something I did because I was into the music and the ideas that came with it, I began to understand that doing such things involved learning and using a growing range of skills.

“Punk was all about doing it yourself, and it was really easy to get involved. If there weren't enough bands playing in your area, then organise some gigs. Did you want to spread info about the music you like? Then publish a zine.”

Kieran Monaghan, now a nurse and member of the band Mr Sterile Assembly, began organising gigs as a teenager in his home town of Invercargill.

“I didn’t know I could organise anything till I learned of the notion of DIY at age 14 or 15. I wanted to see a concert in Invercargill, and there was an interconnected network of bands releasing tapes, of zines full of addresses and other contact details. So I wrote a letter to Dunedin, obtained a phone number and called. I sought advice from locals, it forced me to make connections, I booked halls, made posters and navigated the evening and the clean up afterwards. A massive multidisciplinary project and a steep learning curve.

“I didn’t even know it was an option until it was mentioned. Till that point life was organised via schools, sports clubs, social contracts and institutions such as churches. And then someone said you can make music… well, that changed it all for me. My exposure to the audible riot that punk brought to my ears and mind set in train a process that enabled me to be an active participant in my own existence. It may have happened another way, but this was the way it happened for me.”

“I remember the night before the first all-ages punk gig I organised.” says Wellington-based artist and design lecturer Kerry Ann Lee. “I was so excited that I couldn't sleep. I'll never forget that deranged and giddy teenage excitement. To this day I still can't get over how a 17-year old was trusted with the key to a community hall to organise an all-ages hardcore punk gig, but that's what happened, and regularly for a time.”

Lee also comments on the opportunities punk offered: “Punk afforded being able to see possibilities, which is helpful in all situations as an artist, designer, teacher and citizen. And writing. I never thought of myself as a capital 'W' writer, but then I realise I've been writing and making zines for more than half my life!”

“Punk offered some accidental skills in hindsight, such as learning to be responsible and working with other people to make glorious things from scratch. I guess some people join the army or business school for similar things, but there's a strange compulsion – mostly resisting boredom at all cost – which drove our early activities.”

An activist and drummer for several bands, Ben Knight also started out in the punk scene: “Organising punk gigs was my first experience of any kind of people-organising. Even for someone kind of introverted it didn’t seem too daunting as a starting point because it was always a group effort thanks to the DIY punk community being so full of proactive people supporting each other. And it had pretty clear parameters: organise bands, organise venue, organise gear, organise sound-person, try to make sure nothing is fucked, try to provide a comfortable/safe/inclusive environment that encourages people to look after each other.

“It was a really supportive environment to learn by doing, and things pretty much always turned out OK.”

“When I ended up living with 10 people in a warehouse-type space, as well as having gigs in the lounge (we could fit 200 people at a stretch), we started organising other kinds of events, applying basically the same approach to exhibitions, film screenings, activist workshops, etc. We noticed early on that whenever there were just parties, the house tended to get trashed and there would sometimes be some unfortunate bonehead behaviour – but whenever we organised benefit shows/fundraisers or any event with a social justice focus, people were consistently really awesome.

“So we decided to only organise events with a social cause at the centre, and it was way more enjoyable for everyone – and we didn’t have to spend the next day sweeping up broken glass and fixing holes in the walls.”

“Punk absolutely introduced me to ideas bigger than the musical component,” says Monaghan. “The words of songs, zines and any other artefact were gleaned with the intention of a researcher. Unbeknownst to the reader I was gathering a more broad education and exposure to ideas and philosophies than I’d previously been exposed to. From ways to review and reconsider what food I consumed, to the ways I looked at interactions with others, to ideas of politics, protest, environmental and animal rights, feminism, anarchism, capitalism and so much more.”

The Incompetence of the Mainstream

It’s easy to take punk for granted. It was really when I (the author of this essay) moved into the mainstream that I recognised the value of punk. Moving out of urban activist circles to a small town – albeit one with a strong community organising tradition – I was struck by the weak organising skills evident amongst professionals who were attempting to organise community projects. Generally, they were adept at managing an event, but poor at such things as meetings, managing on-going groups and at maximising the input of volunteers.

After a while, I began to realise that rather than learn methodologies appropriate to community groups, they were simply applying organisational methodologies that they had learned in the workplace. Lacking other examples, the workplace has become the default organisational model for most people. Many of its practices are perceived as characteristic of ‘professional’ behaviour (with ‘professional’ being considered synonymous with ‘effective’).

It is not uncommon when several old punks meet together, even for merriment and diversion, for the conversation to end in a discussion of the inability of managers in the workplace to organise anything properly. While some of this is just the general habit of workers anywhere and everywhere to moan about their workplace, punks’ experiences of alternative methods of organising means they find the level of competence harder to accept. And they often have a strong ability to analyse and decipher what is actually going wrong.

Modern workplaces – at least those of any size – typically have characteristics in common. They are hierarchically organised and well resourced, thus they are able to rely on a workforce whose primary motivation is pecuniary. These workplaces function not because they are well-organised, but because they can throw considerable resources at a problem. They can buy machinery, materials, expertise and workers. While resource scarcity appears to exist in many workplaces, this is mostly a result of misallocation of resources, rather than an overall lack.

Community groups are largely in the opposite situation. They are seldom well resourced and rely on unpaid labour, motivated volunteers and goodwill to achieve goals. Qualified specialists are seldom available, and volunteers often work outside their particular skill set.

The tikanga of the punk movement reflects these characteristics, but is even more opposed to the typical practices of the workplace. The punk movement is actively opposed to hierarchy, save for that which occurs naturally in groups when a person gains mana from prior experience, successes, and a greater contribution of labour. This opposition to hierarchy, and the insistence on a DIY approach, both inspires and, crucially, provides an unusual degree of opportunity to develop skills.

Post Punk

Beyond the basic organising, participants in the punk scene are able gain experience in tasks which would be considered specialist roles elsewhere, as Ross Gardiner notes: “Organising increasingly complex events (e.g. a one night gig with four to five bands, a weekend festival with 20-plus bands, or a tour involving an overseas bands playing multiple venues with 10 or so local bands) will teach you a lot about long-term time management, effective communication, logistics and other things that are essential for other aspects of life, whether it's in the workplace, other hobbies/interests, family and more.”

Kieran Monaghan went from local gigs, to organising Mr Sterile Assembly tours of Europe and Asia.

“In my current role as a nurse – I’m also in a management position where I need to manage rosters, annual leave, sudden crisis and calamity – I’ve joked that if I can organise from home a musical tour through eight countries – that I must have developed the skill set to do my day to day role. These trips go across multiple timezones, languages, currencies, local expectations and bureaucracies (which have to be subverted and diverted); and there’s accommodation, transportation, and facilitating new connects in distant places to be arranged.”

Punks often take the methods of the scene into other projects, outside the punk movement. Gardiner has had a lengthy involvement in organising the Manawa Karioi Ecological Restoration Project based at Tapu Te Ranga marae in Island Bay, Wellington.

“It's been run for 30 years on a very low budget, and really struggled to get things done at times. But applying many of the ideas and skills that make people feel involved and part of the project rather than being just another volunteer has seen the project flourish again in recent years. So fuck you! Planting trees is punk!”

Experience in the punk scene takes people to all sorts of places. After taking part in the Occupy movement, and in the collective that developed the Loomio decision-making software, Ben Knight was involved in setting up 19 Tory Street, a community gallery space in Wellington.

“It was intended to be as accessible as possible, basically just providing a free space for anyone to organise any kind of community event. So it reached well outside the punk community, and it was amazing to see all kinds of people start spontaneously using it. There were lots of art exhibitions and performances, but also it was being used for organic vege box distribution, embroidery classes, book launches, film nights, Spanish lessons, yoga classes, all kinds of stuff.

“Like loads of people involved in the punk community, it was an entry point into activism and community-oriented work where solidarity and mutual aid take lots of different forms, from protest stuff, to helping set up a tech co-operative, to growing food and swapping veges with neighbours.”

Organising gigs and publishing zines led Kerry Ann Lee to a career in academia, recognition as an artist, and to organising large-scale events such as the 2018 Asian Aotearoa Arts Huí.

“The magic combination of art, music and politics is something I still love. The details of which have changed over time but there's still the core of outward-facing action, surprise, urgency, concern, fire and delight. I look for these things in unlikely places: in the academy, in public places, in communities, in nature, in archives, and non-punk spaces.”

Touring overseas brought Kieran Monaghan into contact with punk projects that had expanded far beyond a musical or artistic scene.

“We visited a city called Blitar on the island of Java to play a couple of times. There was the most impressive DIY network I’ve ever witnessed. There was no social welfare, no social safety net, rigid doctrines commanding how one behaved and dictated how one engaged socially. The punk community broke all those rules yet they activated an idea to challenge these norms while creating both entertainment, education and employment in an independent space.

“After the death of a member of the group’s father, they gained access to a piece of land by a main road. Here they built a punk carwash, determined to do the best job as a means to challenge the local perceptions of what a punk was like. Here they could show themselves to be diligent, hardworking, self-sustaining while still maintain their identity. In addition, this place provided space for an extended family to live on-site, a space for a screen-printing workshop providing services to other local needs, a small computer collection to teach the use of technology as well as do video production, a music rehearsal space for local kids to hang out and play. And a hairdressing space for the young mothers to create income.

“From a western perspective this may seem small and pandering to other local norms and perceptions, but in this actual environment it was radical and practical.”

Resource Efficiency

The punk movement was, and is, absurdly under-resourced, which is one of its greatest strengths.

The punk economy functions because it has a high level of motivation and ingenuity. Punks are adept at using free or low-cost materials, scavenging, finding opportunities others haven’t noticed. Cheap flats, warehouses and basements provide venues and living spaces. Dumpsters provide food and materials. Social welfare and dead-end jobs provide a financial base. Actually, punk is a bit like the real manifestation of the picture capitalist propaganda paints of the ‘free market’ – a participant-led, highly efficient producer of goods and services at low cost.

Punks who move into the realm of the establishment are often stunned by the expectations of required resource levels to complete a project. After the challenge of producing successful events on three-eighths of fuck all, one becomes faced with the difficulty of finding something to soak up the excess money and comprehending why a consultant gets paid so much to do a worse job than your mate could do in their spare time.

Ben Knight remembers being in this situation at the 19 Tory Street space: “We got some funding from the city council to host a ‘community preparedness’ workshop with people from civil defence. Since everything was volunteer-run and DIY on the cheap, the funding that the council assumed would be needed for a one-night workshop was basically enough to cover the running costs of the space for two years.”

Kieran Monaghan also comments on the bare bones nature of organising: “Exposure to punk was certainly my gateway introduction to self-organising and organising spectacular events on the most minimum budgets.”

The lack of resources leads punk to depend on the creation of extensive networks. Punk was globalised through phone, mail, and face-to-face networking expedited by travel to gigs and social events well before the internet. For punks, effective networking is not a preferable option, but an essential one. A capitalist enterprise that fails to network effectively may survive nevertheless. The need to share scarce resources means a punk scene that doesn’t network effectively is utterly doomed.

Ross Gardiner comments: “Punk’s sense of community and doing things yourself rather than sitting back taught me that those things are really important, and made me get involved in other things as I realised that you can achieve a lot with little money and meagre resources. We work together to achieve what we want.

“Loaning gear and helping out in all sorts of ways makes the punk scene happen. I've taken that attitude and applied it to other parts of my life.”

What is to be done?

In addition to achieving its own internal goals of creating an accessible social support group for working class and marginalised people, punk has acted as an informal training ground giving people the opportunity for collective and autodidactic education which has empowered participants to contribute to many projects outside the movement itself.

It remains to ask, not what punk has done for society, but what society can do for punk?

Possibly, the answer is fuck all, really. Society has accidentally provided the economic and material pre-conditions for the formation of a punk movement by embracing a ridiculous ‘free-market’ ideology which creates the inequality and continual economic crises that spawns punks. Consumerism provides a wasteful material economy that provides opportunities for scavengers, and state bureaucracy creates loopholes that the cunning can exploit.

Japanese punk band The Blue Hearts, in their song Linda Linda, sang “I want to be beautiful – like a sewer rat”. Modern urban society unintentionally creates ecological niches for both rats and punks. Like the unwanted pests that it identifies with, punk thrives in the ignored and scummy physical, intellectual and social corners of society.

The occasional ability of punks to succeed in obtaining recognition or funding from the establishment, is not perceived as a desire on the part of the establishment to be inclusive of punk, but a testament to punk’s ability to produce geniuses, and to society’s frequent failure to understand who it is dealing with. For punks, success in the mainstream is seen as either an unintended consequence of ingenuity, selling out, or pulling off a bit of a scam.

Perhaps the one thing that could be of benefit to punk would be an increase in social welfare payments, allowing people the financial freedom to be active citizens – organisers, artists, activists and crafters – rather than being focused on sheer survival. The dole has often acted as an effective funding stream for punks (and other creatives and activists) due to its relative lack of bureaucratic requirements. It helps that, unlike more targeted arts and community funding, it is of little consequence that the funders don’t really have a clue where the money is going.

And while there may be little the mainstream can offer punk, but there are potential benefits to some on the fringes of the mainstream in better understanding punk methodologies. Learning from punk may make the mainstream a little less crap.

Punk’s success as a movement rests on a system of values and methodologies that wider society is unable to understand or take seriously. It is clear that should wider society choose to include punk – to promote it, fund it and incorporate it into its own structures – it could do so only by demanding compromises from punk that would close off the opportunities that punk affords to many, and cause the movement to become immediately irrelevant.

Thank fuck that’s not likely to happen.

ENDS

This work was commissioned by Wellington’s Pyramid Club and funded by you, the taxpayer. Amazing, but true!

Sam Buchanan is an old punk and anarchist living in Paekākāriki. He has worked as a chef, journalist, National Park ranger, communications manager, shop worker, teacher, gardener, and engineering draughtsperson, and grumbled about the management in each of those positions. He likes comics, Sichuan food and fireworks.