A banker’s rump advice for an artist at a loose end - Murdoch Stephens

1.

One side of the road is the rump of Mt Cook – not a mountain, not even much of a hill. There is the dross of the Navy yards. Then there is a weird Massey accommodation block that I rarely see anyone in. Tennis courts, too, but set up a little higher than street level, with a grass embankment that architects probably promised people would sit on but on which I've only ever seen cans of Cody's resting.

We cycle up Taranaki St, walk through the park from Tory St, wait for friends at the corner of Webb St.

It's not as central as where Happy sat on the corner of Tory and Vivian, nor as quaint as Freds in the waning church on Frederick St.

Now I can see Wellington High and there's signs for Massey University itself, then there's the pedestrian crossing and twin bus stops.

There are cinder blocks buildings with water stains and hopeful car parts franchises with signs so effusive you know they've got something filthy that they’re hiding, something to fear.

This is a kind of home, kind of familiar.

In the door and up the stairs. Art, sound, light. The show hasn't started. Capacity is lower these days... who knows forty-five? More? Your old flatmate is on the bar. The woman from that band is on the door. The opening act has started. Or it is finishing? It is another night at Pyramid Club.

You close your eyes to breathe it in and then... it stops. It all stops. You open your eyes. Pyramid Club is empty.

Pandemic! Quarantine! Panic! Death Disco!

Dan ambles up to the stage and – as if your opening eyes are the cue – he addresses the audience in that wonderful circus master voice he sometimes uses to introduce bands:

Part of the effect of the Covid19 shutdown has been a forced reflection on the way we work, what we make, and why we do the things we do.

You look to the sound desk. Jonny or Thomas nod back to Dan. You turn back. Dan has gone. His words linger:

Covid19 shutdown:

a forced reflection on the way we work,

what we make,

why we do the things we do.

2.

Shit! I've forgotten to introduce myself. I apologise for my arrogance.

Some of you know me but some of you don't: I'm Murdoch Stephens. I'm on Facebook and Twitter but not on Instagram. Look me up – friend of a friend – you'll probably recognise my muttony countenance; a face with all the charm of last Sunday’s silverside. Just kidding. I’m holding it together alright for my age. Moisturiser, no kids to speak of; it’s not rocket science.

You will have seen me around these kinds of gigs in the last fifteen years. Beer in hand, legs crossed, ponderous expression like I understand what the musician is really trying to do.

Let me tell you a bit about myself and my art practice.

I oversee the production section of the Reserve Bank of New Zealand. If that isn't a Wellington job, then I don't know what is. Central-fucking-government, 2020 y'all.

What does the production section do? Simply, I make money. Like, literally.

I mean, someone has to make it, right?

It's a kind of fantasy job: surely you've had a vision of our stacks of cash at some point in your life? The beautiful, blushing pallets of sheets of NZD$20 notes. Then the giant guillotine slices the bills into wallet-sized portions.

The job pays well, even for Wellington. I joke that I make $800 million dollars a year. No-one really laughs at that as much as I do. They don't even laugh when I raise my brow and confide that I'm making a mint.

Some people would find my work at the Reserve Bank abhorrent. Do I care that they mistake the production of money with capitalism itself? Hell, even the communists had rubles to smooth out their trading.

Other people find my work at the Reserve Bank to be the absolute pinnacle of craft and art.

Think about this proposition before rejecting it!

Proposition: hard currency is the ultimate art work. Evidence: the design on money is incredibly unique, almost impossible to counterfeit, validated by the latest technologies, authenticated with a signature, and – best of all – is accepted everywhere in direct exchange for goods and services.

Imagine having that power as an artist!

Imagine if an artist could walk around with a notepad and pen and wherever you went you could dash off a sketch and a shopkeeper would immediately know what it was worth and would accept it in exchange for a car stereo or shopping trolley of groceries. Your landlord? Why bother... just whip out a bigger notepad and stroll up to any old house with a For Sale sign and create an art or two. The house owner would recognise the signature, the inimitable art and the

value that you've written on it. It'd be like a cheque book with no limits and instant identity verification.

OK, so it's a bit of a fantasy that you could run around and use doodles to pay for things like we use cash. We've all probably heard of those stories of desperate artists who barter work for a few months at the Chelsea Hotel or even a few comic books.

Artists who want to act like they own the money printing press – the mint – usually have to work through the market to achieve their ends: get a dealer, get some buyers, establish a style that buyers will recognise, maintain a limited demand, and all the other little tricks that make art prices grow.

So what does this mean for those people who gather at Pyramid Club?

I am here to advise Pyramid Club’s community to not go back to the old ways of making art but to be like me: get rid of all the art that has taken up your time and space and set about making your own industrial art-minting zone.

It doesn't just have to be pretty pictures on polymers that I make.

Music can be a mint, too. Remember when CDs of greatest hit collections sold for $34.95 at the CD Store. An absolute mint. It isn't exactly the same as what I do, but it is pretty similar. Reproduced as many times as you want, almost indestructible (well, not really), instantly recognisable with the band's brand and a whole legal system set up to prevent counterfeits.

I'm telling you, Pyramid Club community: it is time that your art paid off, that it transmogrified into the form of money. Make your art mimic that which is pure value.

Is anyone with me?

Anyone?

3.

Okay. I get it.

One reason I love the Pyramid Club is that most of the time it feels like the musicians are trying to do the complete opposite to what I do at work. No-one seems to be putting ‘making a mint’ forward as their number one reason for being at Pyramid Club. (Sure, there's a door charge - $10, maybe $15 – but no-one is going to be buying a house in Kelburn on those receipts).

If anything, it feels like people at Pyramid Club are 100% opposed to the so-called art that I am making at the Reserve Bank.

Where I'm making a mint, y'all are defacing the currency.

If I am printing stacks of pristine, identical units of perfect currency, y'all are pulling out vivids and drawing tattoos and monobrows on Queen Elizabeth II and Sir Ed.

You're more like the Canadians who Spock their $5 notes. You see the art in the vandalism, whereas I see it in the original perfection of the design.

I'm not trying to be a bastard. You knew what you were getting into from the start and so did I. But it is true: you want to deface the currency. The whole idea of annihilating what we’ve inherited is somewhere at the root of what compels your art. I don’t need to be Carl Jung to figure that out.

These are the two poles of people who make art: first, those people who want to produce art that can be exchanged for the necessities of life. Those are the people I've already described. Those are the people who are making a mint or are wanting to. To make a mint you’ve got to make something that stands the test of time and can be exchanged. The second group of people who make art are those who mostly want to challenge received wisdom and culture.

This second group of people are in a trickier spot than those who, day in and day out, work with the repetition of making art that is like money. For example, how do you keep defacing a currency without the repetition turning perverse? You do something once and it's easy, but repeat the same act and you'll start to get a name for yourself. You might even be able to sell your version of the Spocked money for a little premium. Put it on a t-shirt. Make sure wikipedia knows you were the first to do it. Print it on a coffee mug. $17.99.

The person making a mint does everything they can to build up an identity like the Governor of the Reserve Bank which is at the base of their value making exercise. But the person defacing the currency has the strenuous job of also defacing their own self as currency.

For these folks, luckily, there is also an arch-provocateur: Diogenes of Sinope. Diogenes is perhaps the most famous of the Ancient Greek Cynics: a homeless, hilarious band of philosophers from the time of Plato. The first rebellious act of Diogenes was literally to deface the currency – his father, as legend has it, was like me: the person who oversaw the production and storage of currency. Like the Spockers of Canada, he literally changed the face on the currency. Unlike the Spockers, the coins were rendered unusable by Diogenes. He (and his father) were exiled, leading to Diogenes' broader project of defacing the currency of received wisdom, virtues and morals.

Artists who strive to deface the currency are those who would rather crap in an art gallery than hang their work there. They are like the Nietzschean adepts who want to upend all values: their phrase for defacing the currency is to transvaluate all values (though I prefer the translation “transmogrify values”). These folk don't want to soothe the aching bones of the world, but to rouse people to spot conceit and ineptitude. The spirit of defacing leads to a spiking of a pop song with an atonal hum, experimental literature that refuses to develop characters or a plot, or the painting that shreds itself the second it is sold at an auction house.

If defacing the currency is the aim then there are a lot of art practices of mimicry that you might not really think deface anything at all.

Is it really defacing if you are documenting your art and compiling it in a CV?

Is it really defacing if your paintings of the most grotesque scene imaginable sit neatly above a collector's mantelpiece?

What if your improvised ensemble is recorded and released on CD-R?

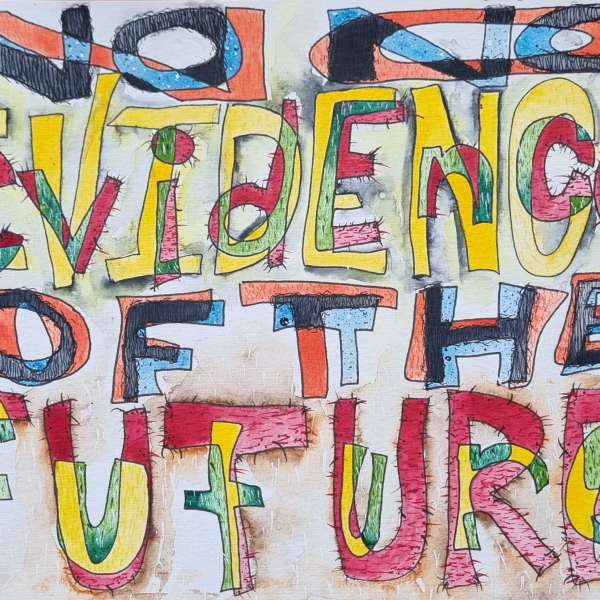

Weren't the punks supposed to have no future, rather than wind up on I'm a celebrity... get me out of here!?

It is easy to position Johnny Rotten as the best example of someone who mimics defacing the currency, but who was really interested in making a mint. Rotten was eventually the artist who said he was selling the image of rebellion in his own attempt to make a mint.

Counterculture isn't separate from the consumerist culture just because it sports icons of resistance or spouts revolting slogans. The counterculture is churned into the culture, feeding it as a symbol of rebellion. And yet if we don't take Johnny Rotten's 'Anarchy in the UK' seriously because it was released by a multinational corporation, then maybe we also shouldn't see his phrase 'ever get the feeling you've been cheated?' at the end of the last Sex Pistols tour as the real truth behind his acts as it is so often touted.

4.

It may have been more polite of me not to write anything: perhaps I should have declined the opportunity to reflect on Covid-19 for Pyramid Club. The whole farce of pretending to work at the Reserve Bank was just as bad. Whatever. It’s a literary conceit... part of defacing the currency is lying about things that make for glorious art. You see: I’m on your side.

But since I'm here and I've already spilled so much ink on the introduction let me go back to the words echoing from Dan on the stage because I really do think there are lessons in the form that money takes.

Covid19 shutdown:

a forced reflection on the way we work,

what we make,

why we do the things we do.

Working, making, doing: they’re material things.

You don't have to be Karl Marx to understand that one of the most useful ways to think about the things that we do is through a materialist lens.

When I write materialism I don't mean the materialism of consumerism, of Madonna as a material girl.

Nor do I exactly mean the physicality of objects as is often meant in material culture in the way that it emerged from the discipline of anthropology. Maybe I am just weary of the anthropology of material culture from outside, rather than the reflection on it from an inside, from the position of the 'we' that works, makes and does things.

If we are really going to reflect on the way we work, what we make and why we do the things we do, we need to have something at stake. There has to be the possibility that something will change based on this reflection.

For me, the greatest barrier to a change in art is people's commitment to the material form in that they've been seeking to deface the currency. (I'm ignoring those making a mint at this point as I don't think that they have felt the same call to reflect on the way they work, what they make and why they do the things that they do).

Why do I publish essays online rather than as anonymous letters dropped in mailboxes?

Who do you paint such gruesome scenes on canvas instead of on the wall of the toilet stall at the Welsh Dragon Bar?

Really: why do we keep on doing the same things we’ve done before? Day in, day out - better lives probably happening somewhere else, Taika’s birthday party in Hawaii or some other FOMO.

We don't change what we do for one reason: we are not simply making a mint or defacing a currency. We are also doing other things. We are also working. We are practicing, improving and testing other limits with the material forms we have chosen.

If the ideas of making a mint or defacing it all aren’t what your art is really about then that’s OK. Think of those ideas as the extremes of a bell curve. Most of us are on the rump not at the extremes. We’re making enough money to keep going and that occasionally means we have to make something recognisable, portable and durable. I turn my ideas into novels that you can buy in Unity. You turn your songs into streamsfor Bandcamp. And at the same time, we’re not hell bent on destroying everything that has come before us. We have affection for some parts of our inherited culture. I don’t want to deface Juvenal’s ‘Sixteen Satires’ or ESG’s ‘A South Bronx Story’.

But just because our art practice has a third way – that we are not obsessed with the horizons of wealth or annihilation – it doesn’t mean we can’t learn something about the enduring materiality of our practices. And, by being able to distinguish the material forms of making a mint from defacing the currency, maybe we’ll be able to call bullshit more often on claims of rebellion that are really just status quo.

So maybe making a mint and defacing the currency do register a little with us.

Maybe we started out in the spirit of defacing, but have ended up counterfeiting some worthless currency.

Maybe we're tired, bored, or a bit sad.

Am I writing essays that try to make sense of the world but always end with upholding the status quo or something just as normie? Should I take up the mouth harp? Why? Why not? (I wrote a little bit about this for the Pantograph Punch a couple of years ago. It was about – other than fascism – how we recognise what is street art and what is just rubbish. Rubbish and resistance merge in the word ‘refuse’ - disobedience and waste. At least that’s what I argued in my Masters thesis fifteen years ago.)

In the middle of COVID19 I asked Facebook for examples of artists who'd made a dramatic break with their mediums to take up another medium.

I offered a few examples: the move from Édouard Levé away from painting to photography and novels after he returned from India. The abandonment of novels and essays by Pierre Klossowski because he did not believe that words could capture the voluptuous emotions that painting and sculpture could capture.

There were some great examples of changes that artists had made but also contention about who had really broken with their previous medium. I was told that Duchamp painted in secret while claiming to be only working in the medium of chess. I was told that Joni Mitchell left songwriting for painting, but has since put out another album.

But then there were also artists who'd made definitive breaks: Helmut Lang from fashion to art, for example. And then there was the example of disabled artists forced to change mediums as their ability to manipulate materials reduced. Our bodies are part of the material world, too, after all.

5.

Alert level negative four... we keep going from total lockdown to absolute freedom and then beyond it. Hiiigh-weeey tooo tha danggger zone...The easiest thing would be to subsume the form of art to the form of life. We would say alert level negative four is to truly live as an artist at every instance of our life. It would be a level of pure spirit. It is not so strange. But maybe that is not a good level negative four... maybe that is level negative infinity? There’s something about negative alert level four that tethers us to what came before. We haven’t dissolved into some pure immanence of grey goo or zen. We are still us. We are still a material form.

Seriously: it is such a challenge to convey what I mean by materiality.

Material forms underwrite money. Economists discuss this materiality over five categories: durability, divisibility, portability, scarcity and recognisability. Money is all of these things.

Here is a checklist for you.

Something to ponder.

Homework for level negative four.

Durable: do you make art that will exist forever or evaporate in a moment?

Divisible: is it easy to split up, understand and exchange part of your body of work?

Portable: can you take your art to the market or is it affixed or too bulky?

Scarce: how many copies of your art are there and do you control it somehow?

Recognisable: how easily can people encounter your art and say, “ah yes this is X”?

Answer them all and ask “why, why, why?” And if you don’t have an answer for why you do what you do – and can stomach the thought – consider that it might be something to do with making a mint.

"Murdoch Stephens is the author of Rat King Landlord (Lawrence and Gibson, 2020) and Doing Our Bit: the campaign to double the refugee quota (BWB Texts, 2018). He wants to thank Mel Oliver and Kelly Pendergrast for - many years ago - reading over associated works that have fed into these ideas. He has never worked for the Reserve Bank, nor been employed by the government, unless you count universities, which you should since they are ideological state apparatus."