From The Archives: a tour of art as process

'Ruby has an exhibition, '(Pū)oro', at Urban Dream Brokerage at 113 Tory Street, from the 15th to the 17th of November. Taonga from the exhibition, including prints of the pukepoto piece featured in this article, are available to purchase now from the exhibition website, www.puoroexhibition.com where opening performance and other details can be found, including an exhibition soundtrack, and interactive booklet. Funds raised through this exhibition will be used to fund Ruby to turn her PhD thesis on the use of taonga pūoro in hauora, into a useable book for her people'.

Facebook event: https://www.facebook.com/events/1736976820493264

Website: www.puoroexhibition.com

I don’t really consider myself a visual artist. As a child, my parents were passionate about providing me with resources to be creative. In visual art, they believed in inate creativity. With music, I had lessons at a community music school. They realised the physicality of music came with a risk of repeated injury, and that the inate side of music needed to be supported so it could flow without any danger of burning itself out. But when it came to creating visual art, there was no discipline, no rules. I was told not to take art at high school. One, because it would take up all my time, and two, because it might take away what I already had. I used to feel a certain kind of loss that I didn’t get to learn art formally at school and what comes after. But in many ways, I did. I had a caregiver who used to let me go for it in her art studio, she called it ‘play’ and it fundamentally changed the way I think about how I use visual art within my wider practice. It’s the space where I get to explore, and most of the time, it’s been the medium that I’ve kept just for me and the people I love... the only people I’ve really made physical things for up to this point.

Dioramas made from adolescence onwards including scenes from favourite books such as ‘Light Boxes’ by Shane Jones, as well as important life moments such as my high school sweetheart moving to Wellington when we were 19 (diorama features Supreme Coffee, Oriental Bay fountain, and Central Park flying fox). Painted ostrich and kāroro (black gull) eggs, and pukepoto artwork of mini tohu.

I use visual art as a sensory way to explore the world(s) I create from. I struggle to clarify what my job or ‘discipline’ actually is. In a te ao Māori way, I can say I’m a haututu, someone who plays around with a range of things; or a kaitoi, someone who feeds and is fed by all things creative. But across te ao Pākehā and te ao Māori together, I think I am a world builder. If I’m going to create something, the first step is to create the world that it comes from. Finding, weaving, and creating the whakapapa of these worlds is where I spend a lot of my time. I always have. It’s no secret that I don’t fully live in this world. That I’m never fully present. Some times I’m hardly here at all. I wrote my first play at fourteen and I remember living in that world for months and months. I made a diorama and a doll of the main character. I still have both. I made a miniature of the physical set in a dollhouse, with each room being a different scene. I’d use that dollhouse to explore all the options of that world, to contain myself within it. I remember falling in love with that feeling, and I’ve been chasing it with every world I’ve ever made since.

Lola, the main character from the school show I wrote when I was fourteen. She had tohu dreams that predicted the future and struggled to tell reality and dreams apart.

The final ‘product’ that is seen by others, is really just the last step of the process for me. It comes easy because I’ve scaffolded so much around it. I’ve kept a lot of those pieces, individual scraps that add up to make a lore of their own. I shared a little mini tour into these archives earlier in the year featuring character sketches from my book ‘The Artist’, including characters that sit within the whakapapa of the book, but who never made it into the book themselves. This includes people from my own whakapapa, Southern atua, and slivers of who I am as a person, and as a narrator.

Character Sketches from ‘The Artist’, including original ideas for Hinepūnui, Hine Pounamu, and Hana.

‘The Artist’ was a world I lived in for years. Really, I still live there. Or I at least return to keep the fires burning. When I was writing the book, I made a set of cards of all the different characters so I could play with the different relationships between people. These cards and their different formations then went into the different chapters of each book to show how the relationships and story develop. I use cards a lot within my creative process to show me things I wouldn’t naturally think of myself. I use ‘divination’ methods a lot in my creative process, because creativity and magic are close cousins in my thinking. I have a set of cards of different taonga pūoro, and a set of our different cave tohu (cave art) from te Waipounamu that I’ve painted in our traditional pigments. I mix and match sets to find new sounds and ideas, it’s a way of randomising and organising themes and data off the computer. It brings tangibility to a process that often feels abstract and intangible. It keeps the sense of play and exploration that I was lucky to have instilled into my process at an early age.

Character cards for ‘The Artist’ used within the final book, but also during the writing process to explore different relationships and connections. The other cards are based around cave tohu and native pigments, using pukepoto and kokowai. I use these to help generate ideas and tap in to the subconscious when needed in my work.

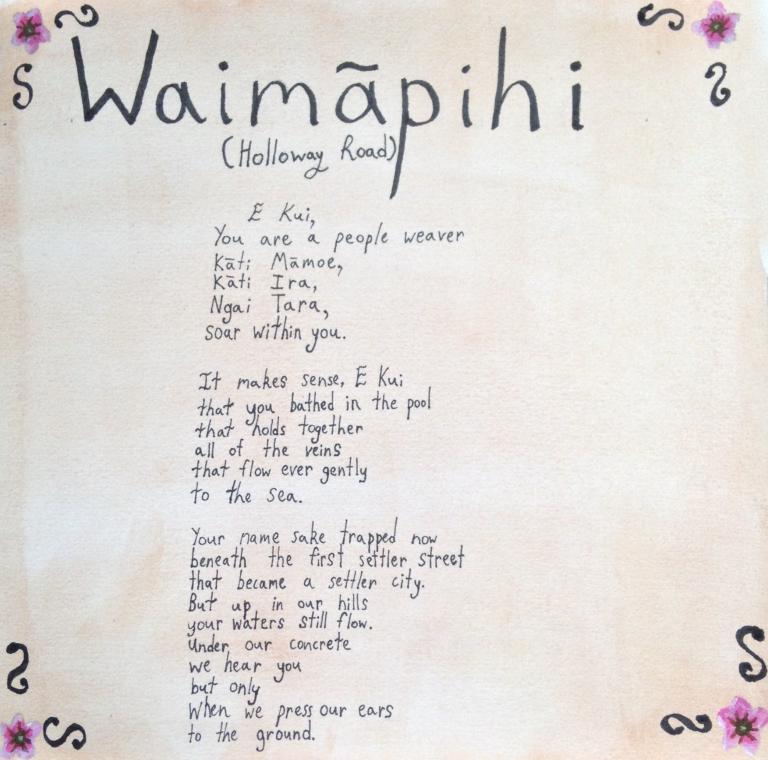

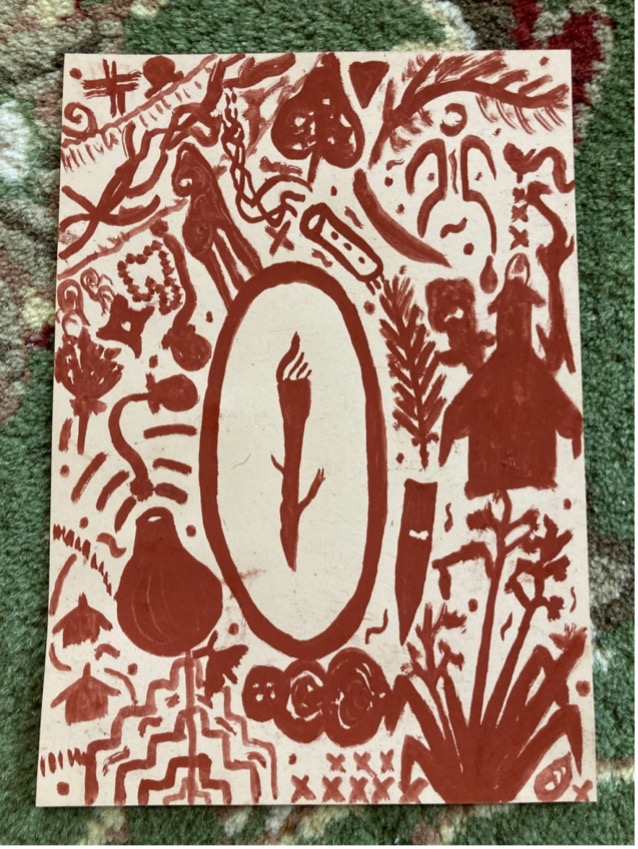

When I was at music school, the DIY aspect of music was a big part of my hustle to live. Being able to make your own promo materials was a way to cut down on costs and gave the bands I was in a point of difference and a way of keeping everything ‘in house’. I’d do posters for other jazz school bands too, and posters for school events. When we moved schools, they got me to make our moving poster. It had a pigeon flying the nest and tiny illustations of all the lecturers standing in the building. After I finished school, I started to work on my own album, ‘Pōneke’, as I moved away from being primarily a session musician. ‘Pōneke’ was an exercise in whakawhanaungatanga between myself and the whenua I live on in Te Whanganui-a-Tara, looking at the histories of Wellington and in particular the journeys of my iwi through this place, as well as those of my Pākehā tīpuna. I took this process very slowly, spending time in these spaces to learn how they sounded and making music that interacted with those sounds. This process also involved creating a piece of visual art for each musical work, as well as a poem to help to pass on that mātauraka; that knowledge. I hand wrote all the poems to make something that would look like a journal or a scrapbook, inspired by how early explorers documented this place. Using it as a way to show how I as Māori perceived time and history within my city. My favourite piece includes a painting of the tipuna wahine ariki, Māpihi, who united Kāti Māmoe, Kāti Ira and Ngāi Tara in Wellington. The Waimāpihi stream in Aro valley is named for her and the place she would bathe. My partner took a photo of me in the bath in our house in Aro valley to use as a refference. Ko au tōku tīpuna, ko tōku tīpuna ko au. I am my ancestor and my ancestor is me, here in this image, her in this time.

Artwork and handwritten poem to accompany ‘Waimāpihi’ from ‘Pōneke’

Working on Pōneke grew so many different areas of my practice and was a catalyst for me creating more visual art to pair with music and pūoro. When Ariana Tikao, Al Fraser and I started Oro Records, one of my jobs became doing our covers. Over time I came up with a “house style” using colours of pukepoto, the sinews of Rakinui, and kokowai, the blood of Pāpātuanuku, on backgrounds resembling the paper of old manuscripts. Honouring all the threads of the label and the projects we awhi. Going into the archives, I found so many aliternate covers and experiments. Many of which were animated and used by Louise Potiki Bryant in our live show where we threaded the album together with poetry and visuals to tell the story of Te Wai Pounamu, and a whanau returning with their pepi to meet the lands that made them. We sought out special permission to use our tīpuna cave art and I felt so blessed to be able to include the lines of our tipuna within this work. My whole life growing up in the north, Māori art seemed to have a focus purely on koru and kōwhaiwhai. But to us as southern Māori, it is our cave tohu that tell us a thousand stories at once. These stories started singing out to me more and more as I drew birdman again and again for the kaupapa, his body subtley morphing each time. One thousand variations of a tipuna. But really, that’s what mokopuna are at heart.

Alternative designs for Tararua album and singles covers, which were later used and animated by Louise Potiki Bryant as part of our tour with Chamber Music New Zealand

This morphed into the time in my life where I was writing ‘The Artist’. After a few snafus with the cover, I decided to do it myself with some kokowai I had traded for taonga pūoro, as is often the way te ao Māori goes. I created a range of alternative covers with tohu from the book, inspired by the cave art seen around first contact featuring horses, boats, and whare, as well as the braided rivers of Te Wai Pounamu and the taonga that populate the book. Again, art is all in one for me. I’ve made a pūoro backing for the first part of ‘The Artist’ which traces the history of Te Wai Pounamu from its inception till the time of te kereme, the Kāi Tahu claim. It’s one of my favourite pieces to perform live because it IS my whakapapa. It’s giving people thousands of years of history and a thousand ways to know you. I feel like I’m difficult to know and understand, but that this work gives people a chance to understand me and my kind.

Alternative cover for ‘The Artist’ featuring different tohu from the book

During my PhD, creating visual art was a way I could make the immense yet intagible workload feel like it had weight, purpose, and took up physical space within my life and the lives of those affected by my PhD. I spent four inensive years studying taonga pūoro and it’s use in hauora and healthcare, with a two year masters looking at the use of taonga pūoro within acute mental health before that. But turning those intensive experiences into words didn’t feel as satisfying as I thought it would. Academia feels so much like one step foward, and then a bunch of arrows from the ivory towers pushing you back. I needed to feel all of the people I’d worked with, all of the oro that had begun to soar behind me, so that I could keep pressing on to get through what I had been tasked to do by some of our kaumātua who had given me so much already. I decided that I would paint all the oro that I had helped bring into the world, and all the oro that had helped to strengthen me to get this far. I went and bought the biggest piece of paper I could get from the art store and started painting tiny individual taonga pūoro in pukepoto, to symbolise all the rangi they will create, and all of the kaipūoro and taonga pūoro behind me and with me on this journey. Each night after finishing my writing and feeling like all my words were trapped inside me, I would sit with my tiny brush and my enormous paper and slowly fill it with taonga pūoro. Across two years of my PhD, this whānau pūoro grew and grew until finally, my PhD was finished. And so was the swirling blue map of my journey.

My giant pukepoto pūoro PhD map, and me being very pleased that it is finished!

Sometimes, words aren’t enough. And for me, this is when the whenua speaks; through tohu and oro. I used the image I made as part of my final PhD presentation, it was barely on screen for a minute. But it was the process that helped to remove those stuck words and feelings from my body, without trying to turn them into words to analyse. A simple and tactile process that must always accompany the complex and the invisible. Pukepoto and kokowai. Matau-raka. One wouldn’t exist with out the other. And now? I’m going to turn my thesis into a book for our people. I’ve missed out on funding, but, He kai kei aku ringa, there is food at the end of my hands. I’ve been making pūtangitangi from natural clay, taonga pūoro that help to pull out stuck emotions. Each one has it’s own whakapapa to its lands, each its own expression, sound and story. I have created 248 of them, that combine as one large artwork. With the sum of its parts, each individual pūtangitangi, available for sale to help fund me writing this book. To hopefully help me to help our whānau.Their oro spreading across the country, as my book grows with them.

Pūtangitangi featuring wheku made from clay from different sites of personal significance, realtionship, and whakapapa.

And those pukepoto taonga painted onto the white page are still waiting... waiting to be sung onto the cover. Waiting for the words for them to sing, to be written. So keep listening, they will be calling for you, soon.

Below is a paper puppet of Hine Raukatauri, atua of music, part of the process I’ve started for my next book...

Kai Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Waitaha

Ruby Solly is a Kai Tahu musician, taonga puoro practitioner, music therapist and writer living in Wellington. She has played with artists such as Yo-Yo Ma, Whirimako Black, Trinity Roots, and The New Zealand String Quartet as both a cellist, and a player of traditional Māori instruments (ngā taonga puoro). She has also worked as a session musician and recording artist with groups such as So Laid Back Country China, Jhan Lindsay, Strowlini Orchestra, and many other artists around Wellington. In 2019 she completed a Masters thesis in the therapeutic potential of taonga puoro in mental health based music therapy, while working in schools, hospitals, prisons and with private clients from iwi around the motu. She also has experience as a composer with pieces commissioned by the New Zealand School of Music in association with SOUNZ, as well as in film work in association with Someday Stories, and the Goethe Institute with Wellington Film Society.

Ruby is also a published poet and has been published in journals associated with many of New Zealand’s universities such as Landfall, Sport, Turbine, and Mayhem. She has also exhibited poetry in Antarctica and New Zealand, and was a runner up for the 2019 Caselberg Trust International Poetry Prize. Additionally, Ruby is a script writer and has found success with her film Super Special which shares knowledge about Māori views of menstruation through narrative. The film aired on Māori TV, and will also air at the LA Women Film Fest.